I’m pretty sure I’m at risk of breaking a cardinal rule of blogging here. That is: to confuse what this blog is about. It is supposed to be about the analysis of politics in search of betting value. However, this post is going to be different: it is about analysis of a major forthcoming political event – the EU in/out referendum – in search of a choice. And it becomes heretical by including an opinion. Well, mine to be precise.

If that makes you uncomfortable, please stop reading now.

The reason I’ve chosen to outline my thinking here is because (a) my view is that this vote is a strategic decision about the future direction of this country for all of us to very carefully consider (it may not arise again for decades) and, therefore, this vote is of supreme and unique importance, and, (b) quite frankly, there was nowhere else convenient I could think of to capture it.

I suppose you could add a – somewhat egotistic – (c) that it might help the few who read it, at the very least, understand the basis of my thinking, and perhaps even influence one or two in structuring theirs.

This is a long blogpost. So I’ve broken it down into eight sections:

- What values might guide your decision?

- How has the EU developed?

- What is the status of the UK?

- What were our renegotiation objectives, and what has been achieved?

- How will the EU develop in future?

- What does ‘Remain’ look like?

- What does ‘Leave’ look like?

- The Choice

Here goes.

1. What values might guide your decision?

Probably about 75-80% of you will have already made up your mind based upon your values. These can include some pretty powerful concepts like the unity of humanity, peace, self-determination, sovereignty, prosperity, tolerance, progress, and open-mindedness.

All of these are good things. However, for many of us, even those who’ve already made up their minds, some of these will be in conflict. So we have to be able to map them to a reference framework to clearly structure our decision.

I think it would be fair to outline mine at this stage:

- Nations are still relevant – humans are social and emotional beings, and we always will be. We tend to naturally identify with social groups that share emotional attachments to land, culture, language, tradition, history and values to a sufficient extent to command our psychological loyalty. These groups used to be transient tribes in the prehistoric age; in the modern age, they are geographically bound nations. They may not be permanent, but any populace has to draw upon a continued sense of civic loyalty to allow the formation of a coherent and stable demos for consensual government. In other words, a group with which we identify with when we say “we”. Democracy requires this for there to be a meaningful engagement between voters and the government through elections.

- Nations do not preclude international collaboration and cooperation – we all live on the same planet. We need international cooperation to address the mutual challenges we have and we should build consent to do so. However, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be very relaxed about national self-governance. Regulatory diversity is a good thing.

- Democracy means accountability – that means the ability to elect, and eject, those who make our laws.

- Sovereignty means reversibility – the ability to both implement a decision, and to reverse it.

The important point drawing these together is this: international institutions, that may be formed by treaties, should not presume they have consent to legislate on our behalf, particularly where the decisions they take may not have popular support and are practically irrevocable through the democratic process.

When this does occur, on issues of significance, it can become a big problem.

In case this all seems a bit abstract, and it is a bit, I will include a few concrete examples later to illustrate the point.

2. How has the EU developed?

This could occupy a (very) lengthy blogpost of its own. But the EU has essentially developed from the (noble) desire to reconstruct the economies of western Europe after WWII, prevent war and ensure a lasting peace.

It is probably not uncontroversial to say that the democratic experience of continental Europe prior to WWII was somewhat mixed. It some cases, democracy and plebiscites had led to fascism and war. It is also fair to say that, in the early 1950s, plenty of European countries, including Spain, Portugal and Greece, as well as all of Eastern Europe, were undemocratic, so there was, amongst many of the continent’s leaders at the time, a dream of a “Europe” that all could rally around.

This led to France, Italy, West Germany and the Benelux countries pooling their coal and steel (the two main tools of war) in the Treaty of Paris in 1951, which included the Europe declaration – the birth of Europe as a political, economic and social entity.

Since then, a number of treaties have been signed by European states. A summary of the powers granted through each is as follows:

- The 1957 Treaty of Rome – created a customs union and the European Economic Community (EEC); a common market of goods, workers, services and capital (plus common transport and agriculture policies)

- The 1967 Brussels Treaty – merged the judicial, legislative and administrative bodies of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), European Atomic Energy Community and the EEC into a single institutional structure

- The 1987 Single European Act – aimed to create a “Single Market”, remove barriers and increase harmonisation and competitiveness. Also codified European political cooperation (forerunner of the common foreign and security policy)

- The 1993 Maastrict Treaty (Treaty on European Union) – created the European Union. Laid the groundwork for economic and monetary union, established the three pillars of the European Union (justice and home affairs, common foreign and security policy and the European Community). It also extended free movement of workers to the free movement of people; EU citizenship created.

- The 1999 Amsterdam Treaty – introduced the idea of a High Representative to put a “name and a face” on EU foreign policy. Incorporated Schengen (borderless travel zone on the continent). Also two major reforms concerning ‘co-decision’ (the legislative approval procedure involving the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union). The EU became responsible for legislating on immigration, and civil law, in so far as necessary for the free movement of persons within the EU. Increased intergovernmental co-operation in policing and crime, and aim to establish an area of freedom, security and justice for its citizens.

- The 2003 Nice Treaty – reformed the decision-making process, necessary to facilitate enlargement of the EU into Central and Eastern Europe, generally by adjusting voting weights.

- The 2009 Lisbon Treaty – EU moved from unanimity to qualified majority voting (QMV) – I will come back to this – in at least 45 policy areas in the council of ministers, made the Union’s bill of rights (Charter of Fundamental Rights) legally binding and enforceable by the European Court of Justice, created a long-term President of the European Council, a High Representative of the EU for Common Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (CFSP), a European External Action Service (serves as a foreign ministry and diplomatic corps for the EU), foresees that the European Security and Defence Policy will lead to a common defence for the EU when the European Council resolves unanimously to do so, gave stronger powers for the European Parliament, and gave a consolidated legal personality for the EU, so the EU is able to sign international treaties in its own name.

Institutionally, the current set-up of the European Union is complex, but a summary of its (seven) main institutions is below:

- European Council – this is where the heads of government of each member state (often called “EU summits”) provide the EU with strategic political direction – it is chaired by the President of the European Council, who acts as a principal representative of the EU on the world stage. Currently, this is Donald Tusk.

- European Commission – executive body of the EU that proposes EU policy agenda, and has a monopoly on all legislation. The President of the Commission is the most powerful officeholder in the EU and responsible for enforcement of EU legislation. Currently, this is Jean-Claude Juncker.

- The Council of the European Union – this constitutes ministers from each member state, which vary depending on the topic. It co-decides on legislation (directives and regulations) proposed by the European Commission and also budgetary matters jointly with the European Parliament through QMV

- The European Parliament – is the “first institution” of the EU and has ceremonial precedence over all authority at European level. It shares equal legislative and budgetary powers with the Council of the European Union and has equal control over the EU budget. Finally, the European Commission is accountable to Parliament. In particular, Parliament elects the President of the Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, and approves (or rejects) the appointment of the Commission as a whole. Currently, its President is Martin Schulz

- Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) – oversees the uniform application and interpretation of EU law, and that the law is observed in the interpretation and application of the Treaties of the European Union

- The European Central Bank – the central bank for the euro; administers monetary policy of the eurozone

- The European Court of Auditors – audits the accounts of all EU institutions

It should be noted there are two other non-EU institutions often confused with the above: the Council of Europe, and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) which is associated with it. Neither of these have anything to do with the EU, despite journalists and politicians often getting confused, except that the Lisbon Treaty incorporated the European Convention of Human Rights into the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, which basically means that the CJEU can now rule on it.

The reason I post all that is to clarify the legal shape and basis of the European Union as it actually is, and the constitutional changes that have in fact already been realised.

Personally, my view (you may disagree) is that it is not too difficult to draw conclusions about whether or not the European Union has stayed on course in following the vision of its founders.

We should be clear what we are voting on.

3. What is the status of the UK?

The UK acceded to the European Economic Community (EEC) and the provisions of the Treaty of Rome through the 1972 European Communities Act. At the time (and for some time after) the EEC was referred to as the “common market”. I.e. a customs union, with no trade tariffs or customs controls on goods moving within the EU, and a common tariff wall applied to goods entering the EU from the rest of the world.

However, the EU is now more all encompassing than the customs union, including the so-called ‘four freedoms’ – the free movement of goods, services, capital and people – that were signed up to in 1972.

We have signed each and every treaty subsequent to our accession, except for the fact we have secured two definitive opt-outs:

- Schengen (we are not part of the common travel area)

- EMU (we do not have to join the euro)

In addition, we have a flexible opt-out (we can choose in or out) on justice and home affairs measure, although we usually do choose to join in, except on matters related to Schengen, and we have a “clarifying” protocol in the Lisbon Treaty on the Charter of Fundamental Rights with respect to its applicability to UK law, although it has been seriously questioned both what this means, and how strong it is.

We used to have an opt-out from the social chapter. However, this was abolished by Tony Blair in 1997.

We are subject to everything else. This includes the common market and four freedoms, and:

- Cross-border financial services

- Social and employment policy

- Energy and climate policy

- Transport

- Consumer rights

- Indirect taxation powers (VAT)

- Competition law

- Agricultural policy

- Fisheries policy

- Regional policy

- External trade policy

- Foreign policy

- Justice and home affairs

- Common Foreign and Security policy

- Common Security and Defence Policy

The EU therefore has a wide-ranging regulatory impact on the whole UK economy, from social and employment law, to environment policy, to agriculture, to regional policy, and on the UK’s net contributions to the EU budget. The ‘single market’ has aimed to develop a single regulatory regime through harmonisation of a common set of technical standards under the jurisdiction of the CJEU, although free movement of goods and people are ‘freer’ than capital and services.

The EU also has a growing role in justice, home affairs and human rights, now under jurisdiction of the CJEU as well.

On foreign policy, article 34 of Lisbon requires us to use our permanent seat on the UN security council to coordinate our action with the EU, to defend its position and interests, and request that the High Representative be invited to present the EU position where one has been agreed. This is already causing frictions as the EU has coveted the UK seat for some time; for example, the UK Government has blocked more than 70 EU statements to the UN, insisting that statements should be presented on behalf of the “EU and its member states”, and not just “the EU”. The EU also has an expanding diplomatic service under the European External Action Service and has set up 139 delegations around the world since the passage of Lisbon.

On trade, the EU represents and negotiates on behalf of all 28 members at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and negotiates free trade agreements on their behalf. Since the passage of Lisbon this includes investment, as well as goods and services.

I mentioned Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) earlier. This is called qualified, rather than simple, majority voting because any decision requires the support of at least 55% of Council of the European Union members, who must also represent at least 65% of the EU’s citizens. This applies to the vast majority of policy areas since the Treaty of Lisbon.

It should be noted that the 19 eurozone countries constitute a permanent qualified majority by themselves, which can outvote the UK if they choose to do so.

Recognising the significant evolution of the European Union since the last UK vote in 1975, David Cameron has had a series of renegotiation objectives since he became Conservative Party leader in 2006.

4. What were our renegotiation objectives, and what has been achieved?

David Cameron’s renegotiation position has evolved. When he ran for the leadership in 2005 his position included a demand for the repatriation of social and employment legislation. This commitment was included in the 2010 general election manifesto, which was held less than six months after the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty, as well as commitments on returning powers on the Charter of Fundamental Rights, and criminal justice.

More importantly, in 2013 he gave the “Bloomberg” speech which set out a vision for the future of the EU.

Essentially, he focussed on the eurozone, how its future might affect the single market, the challenge of EU competitiveness and the gap between the EU and its citizens. It had a number of principles: (1) competitiveness and completion of the single market, and accelerating global trade deals (2) flexibility on integration (3) that power must be able to flow back to Member States, not just away from them (4) a bigger and more significant role for national parliaments, and (5) fairness for those inside and outside the eurozone.

It also made an in/out referendum Conservative Party policy.

The 2015 manifesto promised a renegotiation on that basis, an end to ever closer union, and an in/out referendum on the EU.

David Cameron negotiated a “heads of terms agreement” with all other EU leaders in February 2016, albeit has yet to be put into a treaty, nor has it yet got past the EU parliament. The agreement is summarised here.

Essentially, it agrees the UK is not committed to ever-closer union, introduces a “red-card” to block EU regulations and directives if at least 55% of EU member state parliaments object (but this threshold is so high, it unlikely it will ever be used; for example, a “yellow card” – to delay and rethink – with a much lower threshold of 35% has only ever been used twice), a one-off seven-year temporary brake on social security benefits, indexing of child benefit to the member state the child is living in from 2020, and a reaffirmation on completing the single market in services and increasing competitiveness. On economic governance, it says the euro is not the only EU currency, with mutual respect and sincere cooperation for those who do not share it, and a right for any member state to escalate concerns about the impact of eurozone decisions for urgent discussion in the European Council.

However, there was no attempt at repatriating social or employment policy, no reform of agriculture, no opt out from Charter of Fundamental Rights, no decentralisation of regional policy, no mechanism to flow powers back to the UK parliament, no mechanism to unpick judgements of the ECJ and no reform of EU institutions; for example, double majority voting for both Eurozone and non-Eurozone countries, so a bloc eurozone vote in the Council cannot result in non-eurozone countries having EU laws imposed upon them against their wishes.

In exchange for these small concessions, the UK is now required to facilitate further deepening of EMU across the EU in future, and our veto over this has been surrendered. We have also signed up to further integration and harmonisation in services, including in energy, capital and digital technology.

Once again, we should be clear what we are voting on.

5. How will the EU develop in future?

The European Union has faced two major crises in recent years:

First is the eurozone debt crisis. This was realised during the financial crisis of 2008-2012 by a number of (already overexposed) member states being unable to repay or refinance their government debt, or bail out over-indebted banks, without external help. It revealed a structural flaw at the heart of the euro: a single currency without a fiscal union (e.g. common tax rules, including a mechanism for fiscal transfers) makes it highly vulnerable to external shocks.

Second, is a migration crisis. This has, at its root, continuing serious conflict in the middle-east, north Africa and the horn of Africa where political instability, poor economic prospects and fast growing demographics have created a desire amongst tens of millions to emigrate to Europe. This was given a huge boost by the policy decision by Germany last year to grant asylum to any Syrian refugee that reached its borders. Countries bordering the Mediterranean, such as Italy and Greece, and along the route to Germany, were unable to cope, particularly given their already economic vulnerable state, and many unilaterally reimposed border controls.

Neither of these two crises are going to go away anytime soon.

The EU has led demands for a new quota system to relocate and resettle refugees and migrants around Schengen, which is controversial, and measures to strengthen the maritime security of the EU’s external border.

The EU has also argued for a unified approach to both monetary and fiscal policy, including an increase in transfers from richer to poorer member states to make it work, in a report entitled: ‘Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union’.

This was dubbed The Five Presidents’ Report (because it was written by the President of the European Commission, in close cooperation with the President of the Euro Summit, the President of the Eurogroup, the President of the European Central Bank, and the President of the European Parliament)

You can read a summary here. The full report is here.

It commits the EU to the creation of a ‘genuine Economic Union’, a ‘Financial Union’, a ‘Fiscal Union’ and a ‘Political Union’ by 2025, including:

- A future euro area treasury

- A euro area system of Competitiveness Authorities

- Unified external representation for EMU (e.g. on the IMF)

- A full-time presidency of the euro-group

- A European pillar of social rights – greater integration of labour markets and welfare systems

- Certain aspects of tax policy (e.g. corporate tax base)

In addition, it includes reference to a capital markets union, which will apply to all 28 EU member states as part of completing the single market. This talks about addressing “bottlenecks” like ‘insolvency law’, ‘company law’, ‘property rights’ and strengthening cross-border risk-sharing through addressing the ‘legal enforceability of cross-border claims’. It also references common standards, greater harmonisation of accounting and auditing practices, and deepening integration of bond and equity markets.

The UK will have no veto over this. In fact, we agreed to facilitate it in the recent negotiations and, in any event, deepening completion of the single market is current HMG policy. In my view (and it is only a view) this will be set in motion rapidly following a UK Remain vote.

Longer-term, the Lisbon Treaty includes an aspiration for a common defence policy: “The common security and defence policy shall include the progressive framing of a common Union defence policy. This will lead to a common defence, when the European Council, acting unanimously, so decides.” The EU Commission views this report as a roadmap to a common defence.

The European Parliament also endorsed this report last year which “calls for the necessary negotiations, procedures and reform of the UN Security Council to be carried out to enable the EU to become a permanent member of that body, with one permanent seat and one single vote”.

The risk for the EU (not just the UK) here is that pushing integration to the extent envisaged above begins to undermine rather than strengthen pan-European solidarity. We are already seeing a demand for in/out referendums in other EU countries, with between 41 and 48 percent of respondents in Italy and France saying they would vote to leave. The steady rise in fringe parties on the Left and Right in Greece, Austria, France, The Netherlands, and Sweden is testament to this frustration.

Our votes should pay due consideration to the likely future path of evolution of the EU.

6. What does Remain look like?

In the short term, Remain looks like more of the same. We will retain one EU commissioner portfolio out of twenty eight. The UK Prime Minister will continue to attend meetings of the European Council, we will have 73 of 751 MEPs in the European Parliament, and we will retain 8.4% of the votes in the Council of the European Union.

The main argument in favour of Remain is that of having a “seat at the table”. This is both economic and political: (1) Economic – in that the UK having input into the formulation of EU regulations may reduce non-tariff barriers and increase our access to European markets (2) Political – in that the UK, having a more global foreign policy, and less protectionist trade, outlook is more likely to drag the centre of gravity of the EU towards a transatlantic position that allies with US interests and aids political alliance building; for example, in instigating sanctions against Russia and Iran.

However, there are five particular risks to the UK with a Remain vote in the medium-term, and some are already posing problems now:

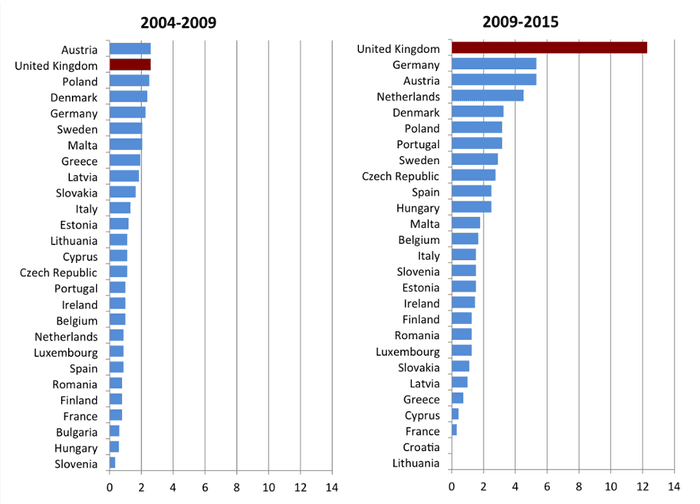

(1) Under the QMV rules of the Lisbon treaty, the 19 eurozone countries now constitute a permanent majority in the Council of Ministers. As they continue to pursue their declared objective of economic, fiscal and political union their interests will increasingly converge, setting the agenda, voting as a bloc and pushing through legislation in the interests of the eurozone. This means that however many times the UK votes against proposals the eurozone will always win and have control over laws introduced here. This is already happening as George Osborne admitted in 2014. The UK Government has also been in the losing minority of votes from 2009-2015 more than four times as often as in 2004-2009, and more than twice as often as any other EU nation.

At the same time as the eurozone is converging, the UK is diverging, with the share of UK exports accounted for by the EU falling from 55% in 2002 to 44% in 2015.

It is hard not to see this divergence continuing. For example, the Economist forecasts that the Asia-Pacific region will account for 53% of the global economy (by GDP) by 2050.

(2) The EU now has a firm constitutional basis and legal identity, established, in particular, under the Lisbon Treaty. It can sign international treaties in its own right. In addition, the CJEU has the power and freedom to interpret the Treaties as it wishes. It is increasingly using the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights to do so; for example, with votes for prisoners in the UK.

–

(3) Both the scope of the EU’s powers, once conceded by treaty, and the laws it passes are practically irrevocable – unless the UK is able to convince the whole of the EU on the former, and, usually, a qualified majority on the latter, to change them. David Cameron tried to renegotiate aspects of the Lisbon Treaty, and got nowhere. This prevents us from being able to change laws that affect all our lives where we decide they are no longer suitable.

For example, the fundamental right of free movement of people does not reflect today’s realities. It dates from when the (then) EEC was a small group of countries with broadly similar living standards. Free movement of workers was limited and not a political issue. Today, in a vastly expanded EU of almost 500 million people, it is. The UK is the largest source of jobs in the EU, with an economy increasingly out of step with the eurozone, and speaks the global language. This poses a major migration challenge, and there is no prospect of it changing. If you desire to be part of an integrated state with a single unified economy, like the eurozone, freedom of movement still makes sense. If, however, you do not want to be a part of that integrated state it really makes no sense whatsoever.

(4) We must continue to accept that 100 per cent of our businesses – large and small – must comply with every aspect of EU regulation in trade, customs, competition, agriculture, fisheries, environment, consumer protection, transport, trans-European networks, energy, the areas of freedom, security and justice we opt-into, and new powers over culture, tourism, education and youth, and aspects of indirect taxation such as VAT.

The 21st Century is likely to include some major technological changes and scientific breakthroughs in genetic engineering, machine intelligence, robotics, mobile web services, smart technology and pharmaceuticals, many of which will occur in the UK. And some of the existing EU directives have proved positively harmful; for example, the Clinical Trials Directive that has badly delayed the testing of cancer drugs.

If we are not able to exploit these to their full through appropriate regulation both we, and the rest of the world, will lose out.

(5) We end up voting for ‘more Europe’. In the UK, it has usually been argued that the European Union is an alliance of nation states, cooperating to achieve what they can’t achieve alone, but ultimately accountable to their own parliaments. The Remain focus on economic matters is telling, because it’s what we want the EU to be about. However, there has been a consistent pattern over the last 40 years of treaty after treaty changing the political balance of power between the member states and the EU. In the UK, we have convinced ourselves that political union isn’t really the objective, or they don’t really mean it, and then it happening regardless. We have then argued for reform – usually unsuccessfully – accepted opt-outs, which then get progressively weakened or watered down, or are surrendered by future Governments, and then replaced meaningful action with periodic symbolic flounces.

–

There’s a clear body of evidence, in my view, that this will continue in future in the areas of foreign, economic, political, social and defence policy, and the EU will continue to expand with the future admission of new member states from Albania, Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro and, potentially one day, Turkey.

–

We must be honest about both the economic and the political realities: there is a continuing intent to build a country called Europe.

–

The Lisbon Treaty was, in my view, a huge mistake. It amounted to a re-badged EU constitution. The rejections of that constitution by the French and Dutch electorates of that constitution in 2005 were almost totally ignored, and the smoke and mirrors that were deployed to get that treaty through – including sidestepping any UK referendum by our Government at the time – were unforgivable. If we had had such a vote, I believe we would have rejected it. Which is why we didn’t get one.

–

There are respectable reasons to vote Remain. Not least of which might include the fact that the current set-up might work well for a number of businesses and industries. However, in my view, there is no such thing as a “qualified” Remain vote. A vote to Remain will be a democratic ratification and endorsement by the UK electorate of all the EU treaties signed to date on our behalf, all the changes in its legal and constitutional basis over the last 40 years, and a tacit acceptance the future direction of integration of the EU. Further, as we were given our own special negotiation, our own referendum, and have agreed to stay, there will be little scope to reopen discussions if we change our minds.

–

This might be our only chance for decades.

–

What you have to decide is if you think our influence will still remain meaningful, real, and if the economic benefits are worth the potential political costs, and loss of direct sovereign control, in voting Remain.

–

Judge for yourselves.

7. What does Leave look like?

The short answer is: it looks like not being in the European Union. It would mean the UK regaining its position in the global pantheon of self-governing liberal democracies. It would become just like all other 163 countries in the world that are members of the United Nations, but aren’t part of the European Union.

That means cooperation and collaboration with both our European neighbours, and global allies, to build a better world, but without remaining a member of a supranational federal union that presumes to legislate for us. It absolutely does not mean isolation, “pulling up the drawbridge”, resurgent nationalism, intercontinental division or any of the other retrograde outcomes that are often ascribed to it.

The most serious disadvantage Leave has is that it is neither in office, nor is it current HM Government policy. So we simply don’t know exactly what “deal” we would get if we did Leave: one has not been negotiated yet.

All Leave can do is develop a series of negotiating positions – as they have already outlined here.

The primary objective would be to “create a new European institutional architecture that would enable all countries, whether inside or outside of the EU or euro, to trade freely and cooperate in a friendly way”.

In particular, to “negotiate a UK-EU Treaty that enables the UK to (1) continue cooperating in many areas just as now (e.g. maritime surveillance), (2) to deepen multilateral cooperation in some areas (e.g. scientific collaborations and counter-terrorism), and (3) to continue free trade with minimal bureaucracy.”

There would be four key aspirations of any renegotiation in my view:

- Primacy of UK over EU law (control over economic regulation, justice, laws and rights)

- Right to sign bilateral treaties with non-EU states (e.g. with India, the US and Australia)

- Right to control who can settle in the UK (via a points systems for students, workers and refugees)

- A new European institutional framework (one that might ultimately recognise an outer tier of a dozen – or more – self-governing European territories and states) for those that wished to join a single trade area, but not a single government

A vote to Leave would therefore be a vote for a common European free trade area, but not a common government. A vote to Leave would be a mandate for HMG to negotiate on our behalf on this basis.

Following a Leave vote, the UK would remain members of NATO and the Council of Europe, but would regain its seat on international bodies such as the World Trade Organisation. The supremacy of EU law and the CJEU would end. Economic and social issues would again be contested in national elections. Our businesses and exports would only have to comply with EU regulations to the extent they wished to export to the EU (just as we must do the same for our US or Japanese exports) but 100% of EU legislation would not apply to 100% of our economy. We could forge partnerships and trade deals across the globe; to give but one example, India is a rapidly growing market for Scottish Whisky – one of our main food exports – but still imposes 150% tariffs on UK whisky imports, because the UK still has no free trade deal with India.

A Leave vote is not a silver bullet. However, it is necessary for restoring democratic self-government. Following a Leave vote, those who made decisions would be accountable again through elections (democratic) and those decisions would also be reversible (sovereign) if they turned out to no longer command popular support.

Neither does Leave mean abandoning our European neighbours. We are a European country, and will remain one. It is in our interests for an enduring and stable political settlement amongst the nations of Europe. We will want to deepen our collaboration in some areas – like in maritime security, scientific collaboration, travel, sanitary controls, regional environmental issues, and cooperate in defence and counter-terrorism – for a better and more secure Europe.

The crucial difference is that this would be done through bilateral cooperation and collaboration and with democratic support. I think our vote to Leave will be positive for all of Europe because it will give leadership to those across the continent who are looking for a progressive future based on decentralised self-governance.

This isn’t something we can’t have. Countries like Australia, Canada, the USA, New Zealand, Switzerland, Norway and Iceland all enjoy excellent economic growth, global influence, the ability to act independently and have strong trusted security links with each other. They are also right at the top of the UN Human Development Index with excellent living standards, and high GDP per capita.

It is, in my view, a very attractive prospectus.

What would the long-term impacts of Leave be?

A vote to Leave would, by definition, involve change to the existing UK-EU relationship. And, given that there is no deal on the table at the moment, it would involve work to reach it. In the meantime, there’s a risk this drives economic uncertainty.

At the end of the day, the UK has been in a close economic union with the EU for several decades, and the business models of internationally trading UK companies have adapted to it. Until the parameters of the future UK-EU relationship are clear, there is a risk that investment, in the short-term, stalls.

However, this uncertainty can be exaggerated. I want to take a quick look at some of the economic arguments.

There have been a number of Brexit studies. These have estimated the net cost/benefit of the UK’s EU membership at anywhere between -5% and +6% of GDP, but all differed in their methodologies and assumptions about life after Brexit. Open Europe’s considered all of these and its own analysis showed “a far more realistic range is between a 0.8% permanent loss to GDP in 2030 and a 0.6% permanent gain in GDP in 2030.”

The respected economists, Capital Economics, also published a report for Woodford Investment Management in February 2016, that aimed to look at this objectively. A few extracts from its Executive Summary include:

–

- “The more extreme claims made about the costs and benefits of Brexit for the British economy are wide of the mark and lacking in evidential bases”

- “It is plausible that Brexit could have a modest negative impact on growth and job creation. But it is slightly more plausible that the net impacts will be modestly positive. This is a strong conclusion when compared with some studies”

- “It is highly probable that a favourable trade agreement would be reached after Brexit as there are advantages for both sides in continuing a close commercial arrangement. Contrary to the claims of many authors and commentators, it is probable that the impacts of Brexit on trade would be relatively small. Moreover, it is certainly possible that leaving the European Union would leave the external sector better off in the long run, if Britain could use its new found freedom to negotiate its own trading arrangements to good effect.”

- “We continue to think that the United Kingdom’s economic prospects are good whether inside or outside the European Union. Britain has pulled ahead of the European Union in recent years, and we expect that gap to widen over the next few years regardless of whether Brexit occurs.”

I would take the official HM Treasury forecasts that households will be “worse off” with a very large pinch of salt. The europhile Fraser Nelson has unpicked George Osborne’s analysis here. First, the study considers no potential upsides to leaving the EU (for example the UK concluding any free trade agreements of its own over its 14 year time horizon to 2030) but does include positive assumptions that the EU will do the same. Second, even on this pessimistic analysis, it is being put about that people will be permanently poorer when it actually shows the difference will be between 29% GDP growth outside the EU, compared to 37% GDP within it. So, the most that can be claimed is that people might not be as much better off as they’d otherwise be.

–

Furthermore, the Treasury has struggled to accurately predict the performance of the UK economy (as has the IMF) on just a 1-2 year horizon in recent years, let alone a 14-year one. But it has also been sharing its homework on Brexit with the IMF and the Bank of England, despite claiming each study is mutually independent, so there’s a real risk that multiple studies are working off the same flawed assumptions.

–

What about the short-term?

–

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research estimates growth next year, in 2017, would be 1.9% if we voted to Leave compared to 2.7% if we voted to Remain.

On house prices, the worst the Treasury has been able to forecast is that a house worth £599,200 in 2018 if we voted to Remain might only be worth only £591,700 if we Leave.

–

None of this represents an apocalypse. It really is minor stuff. And Remain offers no guarantees of strong economic growth either. The most you can say is that there are arguments both ways, that rest upon the assumptions you make, and that the success of the British economy in future is affected by its competitiveness and securing access to global markets through good trade deals.

–

I agree with Wolfgang Munchau, the economics commentator of the FT, who said, “whatever the reasons may be for remaining in the EU, they are not economic.”

–

You have to make your own judgement. Mine is the economic impact of Brexit in the medium-term is financially neutral, but in the longer-term offers much better opportunities for UK growth.

–

In the short-term, if we did vote to Leave, I’d expect an emergency cabinet meeting to be held on Friday 24th June with key representatives from Vote Leave, and a negotiating position to be put out by the British Government over the weekend before the markets reopened on Monday. The real-politik would rapidly change. David Cameron would fly off to see Angela Merkel the following week, and a joint statement would be issued within a fortnight on negotiating intent for a UK-EU deal. Informal negotiations would probably continue with the EU over the Summer, with David Cameron possibly remaining as Prime Minister, at least until the Autumn conference season, to agree its heads of terms with his new Foreign Secretary and Chancellor. We would remain members of the EU right up until Article 50 was invoked and its two year time-frame expired, whereupon the new deal would kick-in prior to GE2020.

–

In the meantime, the UK Government could take a wide range of policy contingency responses to deal with any short-term drop in investment, if it did occur, such as abolishing capital allowances so all capital expenditure is treated as a deductible business expense, or lowering corporation tax to 10%, as David Green has suggested.

–

I do not claim Brexit is risk-free. But I do think the hypothetical risks are massively overblown, and the real risks well within acceptable parameters and manageable. The UK is the fifth largest economy on the planet, the fourth largest military power, has a permanent seat on the UN security council, is ranked first in terms of soft-power, and speaks the global lingua franca. The idea we couldn’t make a great success of self-governance, and exert global influence through it, is for the birds.

–

The UK will be a rich, prosperous and well-off country in the medium-term whether we Remain in, or Leave, the EU.

If we did vote Leave I’d suspect, in five years time, that we’d be wondering what all the fuss was about.–

8. The choice:

Two futures lie before us. I think this is what it all comes down to:

- If you think the single market, as it’s currently constituted within the EU, is Britain’s economic future; that it should be deepened in services, energy and digital, not lightened; and, therefore, that even having 1/28th of the say in the rules is better than none – plus you’re doing well, don’t want any short-term economic disruption and you’re not too bothered by concepts of sovereignty or politics – or you believe we have plenty of sovereignty and influence as things stand – or think that those who disagree doth protest too much, then you’re probably going to be for Remain.

- If, however, you think the UK’s future is global, that the EU will form an ever shrinking proportion of our trade, that it will increasingly be dominated by the eurozone, outvoting the UK, that the limited influence we’ll retain doesn’t compensate for the shared powers the EU has over the UK with its permanent eurozone QMV majority, and that it makes sense for the UK to be represented on global bodies itself independently, and able to control its own trade deals; that you’re confident an independent UK can be just as successful as other smaller anglosphere nations, controlling both its own laws and borders, even if this causes some short term disruption to the existing economic order, but you feel it has to be done, and won’t be that bad, then you’re probably going to be for Leave.

It has been over 40 years since the last EU referendum vote. There may not be another for decades. Therefore, in making a decision, it is entirely appropriate for it to be considered on much longer timescales, and not on a short term basis.

What’s your gut feel? Are you content with the direction the EU is going in? Do you think the EU is the future, or do you think the UK can make a better success of itself independently, and providing leadership by itself? Are you happy to vote Leave on a negotiating position, and agree the details after? Or would you want something more definitive on the table first? What sort of country do you think an independent Britain might be like compared to one that remains as an EU member state? Do you think it matters either way?

All of these are questions that only you can answer.

Personally, the renegotiation for me was the last chance. It was a historic opportunity to put our membership on a sustainable footing. The status quo wasn’t (and isn’t) acceptable. The EU fails my values tests of democracy and sovereignty I set out in Section 1, and there are a number of its policies we are already finding to our detriment. Both the Maastrict and Lisbon Treaties have ratchet clauses open to interpretation by the CJEU, which has been consistently centralising, and the constitution of the EU puts the United Kingdom at a permanent structural disadvantage. I am also deeply concerned at the track record of the EU in pursuing ever closer union, and its declared intent to take this even further in future. The only conclusion I can draw is that the EU – in its current guise – is not willing or unable to accommodate alternate interests. I no longer believe there is any prospect of meaningful reform either for the UK, or for the other nations of the EU, by remaining within it.

There are risks in both remaining and staying. However, faced with a choice between an uncertain future in an unreformed EU and the alternative, which is to leave, to retake control of the full spectrum of policy, set our own laws, and to become a fully independent, global, democratic, free-trading nation, again, the only conclusion I can reach is that it is in the UK’s interests to Leave.

We mustn’t fear to plough our own furrow. And I believe we will be able to have a far greater and more positive influence on leading the future development of humanity, both in Europe and around the world, if we do.

So I will therefore be voting Leave on 23rd June.